History

Beginnings

The Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius came into being as the result of several events which were indirect consequences of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Over the years that followed the Bolshevik revolution, large numbers of Russians, many of them young and forthright Orthodox Christians, left Russia and came to live in the countries of western Europe, especially France, as refugees. Here they came into contact with other Christian denominations that many of them had only read about, or had very limited contact with, in Russia.

Under the auspices of the Student Christian Movement, one of these young Russian refugees, Nicolas Zernov, organised a series of conferences in the English town of St Albans with the aim of bringing together young Eastern and Western Christian students with the aim of discussing points of similarity and difference between their respective theological outlooks and church disciplines.

For most of those present, the Anglo-Russian Student Conferences of 1927 and 1928 were to be the first real opportunity to meet with Christians of other traditions. The Orthodox dimension of the conferences came mainly in the form of Paris-based Russian refugees, though there were also a few Greeks and non-Chalcedonians present. The Anglicans came mainly from the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Church of England, although there was initially some interest from evangelicals and also from Methodists and Scottish Presbyterians.

Opportunities for contact between Anglicans and Orthodox in England had been very limited until this point. At the beginning of the twentieth century there were only five Orthodox Churches in Britain: Greek churches in London, Manchester, Liverpool and Cardiff and the Russian Embassy Chapel in London, which was itself closed in 1917. There were similarly small numbers of English people who considered themselves to be members of the Orthodox Church.

Stephen Hatherley, an Englishman who converted to Orthodoxy in the late 19th century was one such person. Having been ordained a priest of the Ecumenical Partriarchate of Constantinople, he gathered around himself a group of English converts, opening a small church in the town of Wolverhampton in the industrial midlands. His activities so displeased the Anglican authorities however, that following the intervention of the British Foreign Office, Hatherley was forbidden to receive a single further person into Orthodoxy. The church in Wolverhampton was closed and he ended his days ministering to the community of Greek merchant sailors in the newly-opened Greek church in Cardiff.

Another key figure was yet to return to England. Archimandrite Nicholas (Gibbes), another Englishman, had spent time in Russia as Charles Sidney Gibbes, English tutor to the Tsarevich Alexis, son of the last Russian Tsar, Nicholas II. Following the assassination of the Russian imperial family, Gibbes left Russia for the large Russian communities in the Chinese cities of Shanghai and Harbin, taking with him icons and other personal belongings of the Tsar as relics. In China he received the monastic tonsure and was ordained priest, so it was as Father Nicholas that he returned to England, establishing the first Orthodox chapel in Oxford in 1941.

The Early Conferences

There had been limited, though influential, contacts between Orthodox and Anglicans in the period before the St Albans conferences. In particular, valuable work had been done by individual churchmen such as Birkbeck and Palmer.

The Eastern Churches Association, which remains active although small to this day as the Anglican and Eastern Churches Association, was founded in the 1870s under the influence of a group of Anglican churchmen and politicians, among them the then prime minister William Gladstone. This association was intended as an official channel for fostering good relations between the Orthodox Churches and the Church of England. By the 1920s, it already seemed to those attending the St Albans Conferences rather old and stuffy.

The conferences at St Albans broke ground in a number of areas. First, they provided an opportunity for informal contact and the fostering of friendships between Christians of different traditions. Secondly, an opportunity was found for common worship, something not experienced previously, and in fact regarded with great suspicion by many Orthodox mindful of their canons prohibiting ‘prayer with heretics and schismatics’. The daring decision was made to hold a daily celebration of the Eucharist, alternating between Orthodox and Anglican rites. There was no intercommunion, but the liturgy was offered each day on the same altar, and this was seen to provide a symbolic focus for the hope of future full eucharistic unity.

In this light, the conferences of 1927 and 1928 can be considered ground-breaking for their time. Both annual conferences and alternating Orthodox and Western celebrations of the Eucharist have remained features of the life of the Fellowship up to the present day.

It might be worth pointing out at this point that Roman Catholic participation in the conferences (and subsequently in the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius) was not possible in the 1920s and 1930s, owing to the prohibition of Catholics by their bishops to participate in ecumenical affairs. One encyclical issued by Cardinal Griffin, the head of the Roman Catholic Church in England and Wales at the time of the Fellowship’s foundation, actually banned the Catholic faithful from membership of the Fellowship.

The lasting result of the Anglo-Russian Conferences, which actually included many who were neither English or Russian, was the foundation of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius as a means of providing a focus for continued contact and friendship between Orthodox and Anglicans. The two saints were chosen as heavenly patrons reflecting the cultural and spiritual characters of the Fellowship’s two constituent parts. St Alban, England’s first martyr, was a Roman of the second century in whose town the conferences of 1927/28 had been held. St Sergius of Radonezh, a great Russian monastic leader of the fourteenth century is one of Russia’s most popularly venerated saints. His lavra (monastery) of the Holy Trinity at Sergiev Posad (known to many Westerners by its Soviet name Zagorsk) may be regarded as one of the major spiritual centres of Russian Church life.

World War II and St. Basil’s House

Over the next twenty-five years, the Fellowship was to expand the scope of its activities, always driven by the tireless enthusiasm of Nicolas Zernov and its other founders. Annual conferences allowed western Christians to come into direct contact with some of the leading lights in the field of Orthodox theology. Frs Sergii Bulgakov, Georgii Florovsky and Alexander Elchaninov, together with lay theologians like Vladimir Lossky and Lev Zander all began to make regular appearances at Fellowship Conferences, which lasted over three weeks during the summer.

In the years following World War Two, a house was acquired in Ladbroke Grove, London W11 to serve as a permanent base and headquarters. A library was established for the use of Fellowship members, and an Orthodox chapel was opened in the house, dedicated, like the house, to St Basil the Great. The chapel, opened by Metropolitan Germanos of Thyateira, was to serve as the spiritual centre of the Fellowship for the next forty-five years. Uniquely for an Orthodox place of worship, the chapel contained an Anglican altar, outside the Orthodox sanctuary, so that both Anglican and Orthodox eucahristic celebrations might be possible there.

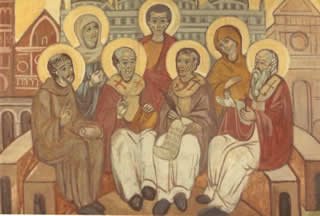

The chapel was decorated with iconographic wall-paintings done by Sister Joanna Reitlinger, a Russian Orthodox nun living in Paris at the time. The purchase and furnishing of St Basil’s House and chapel was made possible through the generosity of many members and friends of the Fellowship, many gifts being made with an element of self-sacrifice. The tempera paint for the icons in the chapel was even produced using eggs donated from people’s food rations (rationing was in force during and following the war).

The war was to have another beneficial effect on the life of the Fellowship. As the war progressed, the Annual conference was replaced by a work camp, in which Fellowship members worked together on farms to assist in the war effort, at the same time continuing discussion and debate in the evenings, and worshipping together each day before work. This all served to deepen the bonds of Christian friendship and Fellowship between members.

In 1948, a young Russian priest from Paris, Fr Anthony Bloom, arrived at St Basil’s House as the Orthodox chaplain of the Fellowship. A year later he was appointed vicar of the Russian Orthodox patriarchal parish in London, and was replaced as chaplain by Fr Lev Gillet, known to many as the ‘monk of the eastern church’, the name under which many of his writings appeared. Both Fr Lev and Metropolitan Anthony, as he was to become, have played a decisive role in the development of Orthodox Church life in Britain, in international ecumenical affairs and in making the Eastern Christian tradition of prayer and spirituality known to a very wide audience. Their many publications are still in print and widely read.

The 1970s and after

t must be remembered that until at least the mid 1970s, the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius provided one of the only forums for Western Christians to encounter Eastern Orthodox worship, prayer and thought. Although the number of Orthodox Christians and places of worship increased in Britain after the war, and particularly after the Turkish occupation of Northern Cyprus in 1974, it was still largely impossible for British people to experience Orthodox worship in English. Not only did the Fellowship organise celebrations of the Orthodox Liturgy in English at its conferences and at other events across the country, it also published its own translations of and music for the Orthodox Liturgy, together with the Manual of Eastern Orthodox Prayers, which remains a classic, in print to this day. Recordings of Orthodox services were made and distributed, and experiments were also made in producing forms of worship for use at Fellowship gatherings which drew on both eastern and western sources. It is not really possible to ascertain how popular these latter orders of service were, but their publication must have made an impact.

Theologically speaking the Fellowship’s impact was also felt. The introduction to the English-speaking Christian world of theologians like Bulgakov, Lossky, Florovsky, Meyendorff and Schmemann often came via the Fellowship and has had an impact which can still not be adequately assessed. Symposia of studies on various theological themes involving both eastern and western theologians were published. These tackled issues such as ecclesiology and the place of Mary. Above all, the Fellowship’s journal Sobornost provided (and continues to provide) a forum for serious theological debate and discussion between Christian East and West.

Unity as Christians is intrinsically bound up with the peace of the whole world, the ‘peace which passeth all understanding’, for which we are bound, as Christians, to pray. The work of the Fellowship is rooted in common prayer and fellowship between separated Christians. It is honest enough to be able to acknowledge differences, both positive and negative. It realises that unity in Christ need not mean uniformity in Christ. The Christian Church existed for centuries without division, but with numerous variations in local church life and practice The one constant factor was a common faith which was firmly rooted in the Gospels and the church tradition, that whole body of teaching, faith and life handed down from the apostles. ‘Unofficial’ ecumenism seeks to regain something of the bond of self-sacrificial love which existed between Christians in the infancy of the Church. It welcomes our unity in diversity as brothers and sisters in Christ with different traditions.

In the Russian Orthodox tradition, this unity in diversity may be translated by the word Sobornost (not by accident the name of the journal of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius). The same word, Sobornost, is also used to translate the word ‘catholic’ in the creed. We believe in one, holy, catholic and apostolic church, but our catholicity does not mean a rigid uniformity. Rather, our unity should have as its model the image of God, a unity of three persons, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, one in essence, undivided and co-equal, but distinct and different as persons.

The question of involvement of the various denominations within Christianity in ecumenical work is, itself, not an easy one. Officially, until relatively recently, Roman Catholics were forbidden to take part in acts of worship with non-Catholic groups. Similarly, Orthodox canon law forbids ‘prayer with heretics and schismatics’. One might, of course, argue what constitutes a heretic or a schismatic, but one might also have the boldness to say that, like other canons, this one has outlived its purpose in a world where common prayer and unity as Christians are of paramount importance. It is no longer really possible to pretend that we, in the western world, live in Christian societies. The brutal fact is that our societies, although some are still nominally Christian, reflect a post-Christian, secularised attitude to life. A great spiritual thirst has led thousands to explore new age religions and non-Christian alternative belief systems in an attempt to make sense of their otherwise empty lives. In the east, societies are frequently dominated by often militant Islamic regimes. Here Christians can find themselves a small, even persecuted minority. In both situations, the Gospel message can only have an impact if Christians do together all that they possibly can to provide a united witness to Christ, and a united defence against hostile forces.

In this context, the Fellowship’s role must be to build up mutual trust, respect, understanding and love between eastern and western Christians. It is best equipped to do this at a small, local level in its branches. In many parts of the world, the Fellowship brings together Orthodox, Reformed and Catholic Christians when they might not otherwise come into contact with each other. This is particularly obvious in places like Russia, Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria, where western Christians are often perceived as a dangerous group of heretics with whom unnecessary contact should be avoided. Incidentally, this estimation usually also includes Orthodox Christians in the west as equally tainted and suspicious.

The Fellowship can help to overcome the suspicion which results from a lack of knowledge of the other. By meeting, common prayer and study, by education and information through our journal, information service and conferences, we have a role to play. In very practical terms, the capital realised from the sale of St Basil’s House in 1993 allows us to award grants of about £30,000 per annum to support projects which will increase east-west Christian contact and understanding. In recent years, by way of example, we have supported scholarships for Orthodox theological students to study in western university faculties, we have funded publications of western theological works in Russian and Bulgarian, and of Orthodox works in English, we have supported theological libraries and schools in Russia, Bulgaria and Britain. We have funded two British conferences, one on Orthodoxy and the future of Europe, the other on the history of Anglican-Orthodox relations. We have supported exchange visits of icon painters and scientists to and from Russia and Romania and Britain. We have provided numerous small travel grants to help facilitate study visits by Western Christians to traditionally Orthodox countries.

In all of these areas, we are able to build up a number of friendly contacts which remain for years. As the participants in the Anglo-Russian Student Conferences of 1927/28 discovered, it became easy to see the urgency of the need for unity once one had developed a personal relationship of trust and friendship with the other: ‘Cor ad cor loquitor‘, as Cardinal Newman wrote – ‘heart speaks to heart’.

For more detail about the history of the Fellowship read The Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius: A Historical Memoir by Nicolas and Militza Zernov published in 1979 to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Fellowship.